Saved by the Bell

The Great Vancouver Fire of 1886

Note: I’m working on a series of short essays about the history of Vancouver. This is the first of several I’ll be posting here over the coming weeks.

Last year, I was fortunate to work as a research assistant on a project about the history of fire in American cities under the supervision of Daniel Immerwahr. This essay is inspired by his research.At midday on June 13, 1886, the bell at Vancouver’s St. James Church began ringing vigorously. The congregants had gone home for lunch after a morning service, but Reverend H.G. Fiennes-Clinton needed to get their attention. The young city was ablaze, flames travelling down the wooden sidewalk of Hastings Road “faster than a man could run.”1

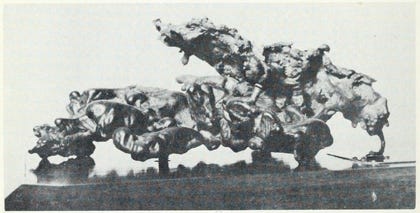

Fiennes-Clinton didn’t have long to get the message across. A few minutes after he started ringing, the church was aflame. “The bell, in the tiny cupola on the ridge of the roof, melted with the heat, dripped in globules to the earth below, where they solidified into a shapeless mass,” wrote city archivist J.S. Matthews.2

The Great Vancouver Fire, as it is now known, wasn’t entirely unforeseeable. In 1885, there were only about 900 European settlers in the area surrounding the Burrard Inlet.3 European settlers hoped to clear land to expand the nascent city, and the fastest way to clear land was with fire. By the morning of June 13th, “the whole of the hill above Victory Square had been afire for weeks with clearing fires.”

It didn’t help that the summer of 1886 was especially hot and dry. Puddles along Carrall Street had long dried out; heaps of dried-out timber collected on the outer edges of the city, “up to three storeys high in places,” as trees were felled to make space for more people.4 The city had become a kind of waiting tinderbox.

Yet the Vancouverites kept burning. In June, city officials planned a clearing fire in the city’s southwest, intended to make space for a roundhouse. It had been announced only a year before that the township of Granville (soon incorporated as Vancouver) would be the west terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway, and the trains would need a place to turn around. At ten o’clock on the morning of June 13th, the railroad workers were fighting an out-of-control blaze, though they didn’t “even dream that anything so serious as afterwards happened would occur.” By afternoon, the workers had been forced to leave the camp. Several fled into False Creek, where Squamish people from the creek’s southern side came to rescue them in canoes. Three men from the work camp, who had volunteered to help fight the fire, were never found.5

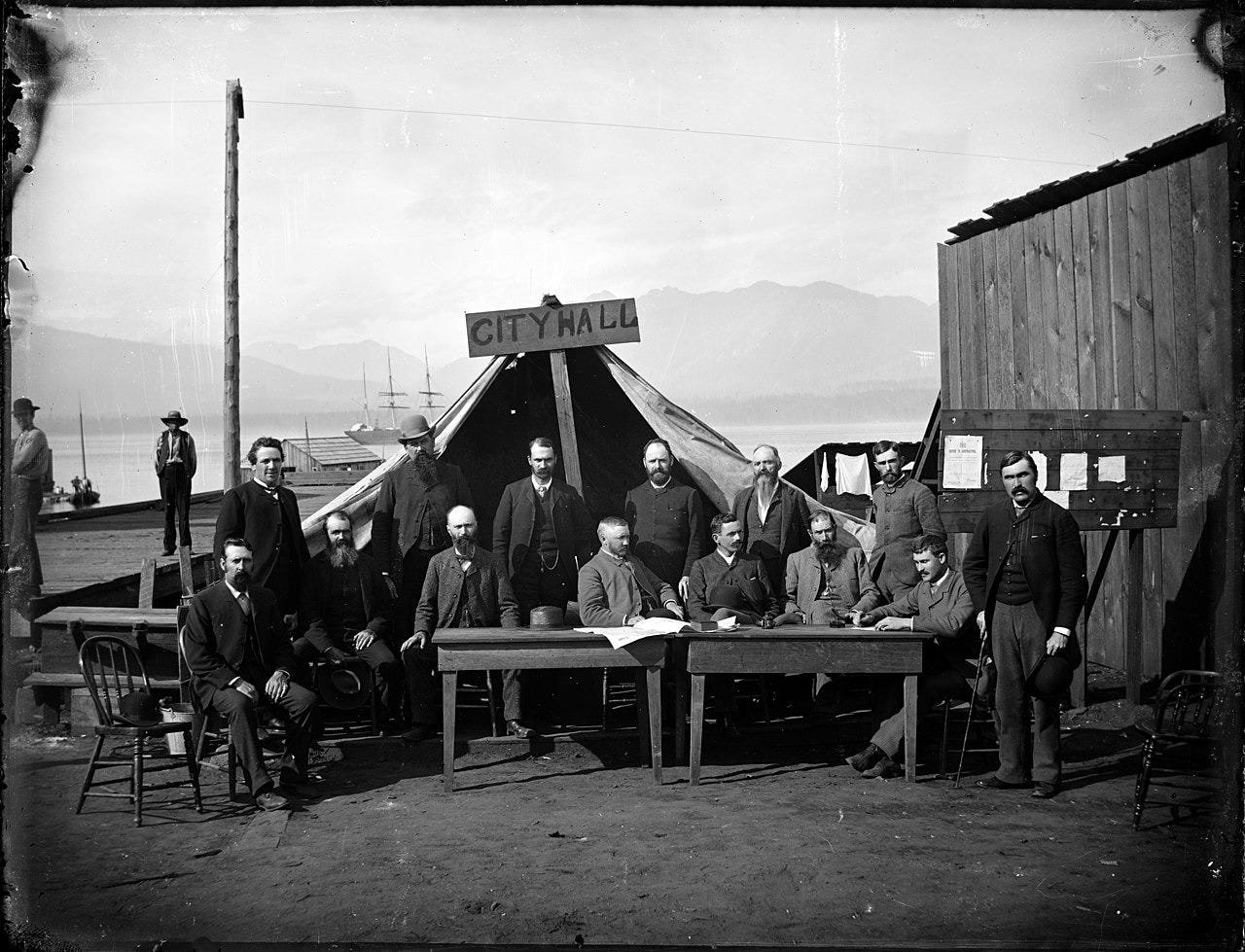

By the time the fire died down, close to 1,000 buildings had been destroyed.6 The City Council and Police Department set up in a makeshift tent and sent telegrams to Central Canada pleading for help. The city rebuilt quickly. A local mill offered free lumber to any inhabitant who had lost their home, and within six months, about 500 buildings had been erected.7

Vancouver wasn’t alone in its fiery unravelling. By the late nineteenth century, North America was experiencing major urban fires almost every year, in large part because of the rise of hastily built, tightly packed wooden neighborhoods. As historian Daniel Immerwahr notes, the widespread use of wood may explain why American fires were “eight times costlier per capita than European ones” by the turn of the twentieth century.8

The Great Vancouver Fire may not be unusual in substance, but it is unusually absent from the city’s narrative of itself. In many American cities, the great fires of the nineteenth century are remembered vividly. “Atlanta, Lawrence, San Francisco, and Portland, Maine, all have flags featuring phoenixes,” writes Immerwahr. Novellists like E.P. Roe and Horatio Alger Jr. spun out motivational narratives of conflagration for the general public.9

The Great Vancouver Fire, by contrast, has faded steadily into oblivion. Vancouver schoolteachers rarely mention the fire that more or less destroyed the community only 140 years ago. The melted remains of the St. James Church Bell are held in the Museum of Vancouver, a scarcely visited collection in the basement of a scarcely visited planetarium. It resembles one of Dali’s clocks; some grotesque mushroom; a postmodernist bronze sculpture at MoMA; anything but itself.

In part, this amnesia can be attributed to the city’s small population at the time of the fire. Vancouver had fewer than 15,000 people in 1886; Chicago had over 300,000 in 1871, the year of its first major fire. American conflagrations were larger, and American cities had more people to carry the memories forward.

In another sense, the fire’s disappearance is part of a deeper urban forgetfulness. “Vancouver has been called a city without a history,” writes urban historian Daniel Francis, “partly because of its youth but also because … it seems to change so quickly that it leaves no trace of itself behind.”10 In 1886, the city quite literally left few traces behind.

Major J.S. Matthews, Vancouver Historical Journal (City Archives of Vancouver, 1960), 31.

Matthews, Vancouver, 32.

Norbert MacDonald, “A Critical Growth Cycle for Vancouver, 1900–1914,” BC Studies, no. 3 (Fall 1969): 26.

Lisa Smith, Vancouver Is Ashes: The Great Fire of 1886 (Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2014), 2–5.

Matthews, Vancouver, 30.

“Crab Park: The Great Fire,” Vancouver Heritage Foundation, last modified April 15, 2019, https://placesthatmatter.ca/location/crab-park-the-great-fire/.

Lisa Anne Smith, Vancouver is Ashes: The Great Fire of 1886 (Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2014), 83.

Daniel Immerwahr, “All That Is Solid Bursts into Flame: Capitalism and Fire in the Nineteenth-Century United States,” Past & Present 265, no. 1 (November 2024): 99.

Immerwahr, “Capitalism and Fire,” 119-121.

Daniel Francis, Becoming Vancouver: A History (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2021), 5-6.

interesting - thanks agarwhale:)