Paper Cities

The fire insurance maps of Charles E. Goad

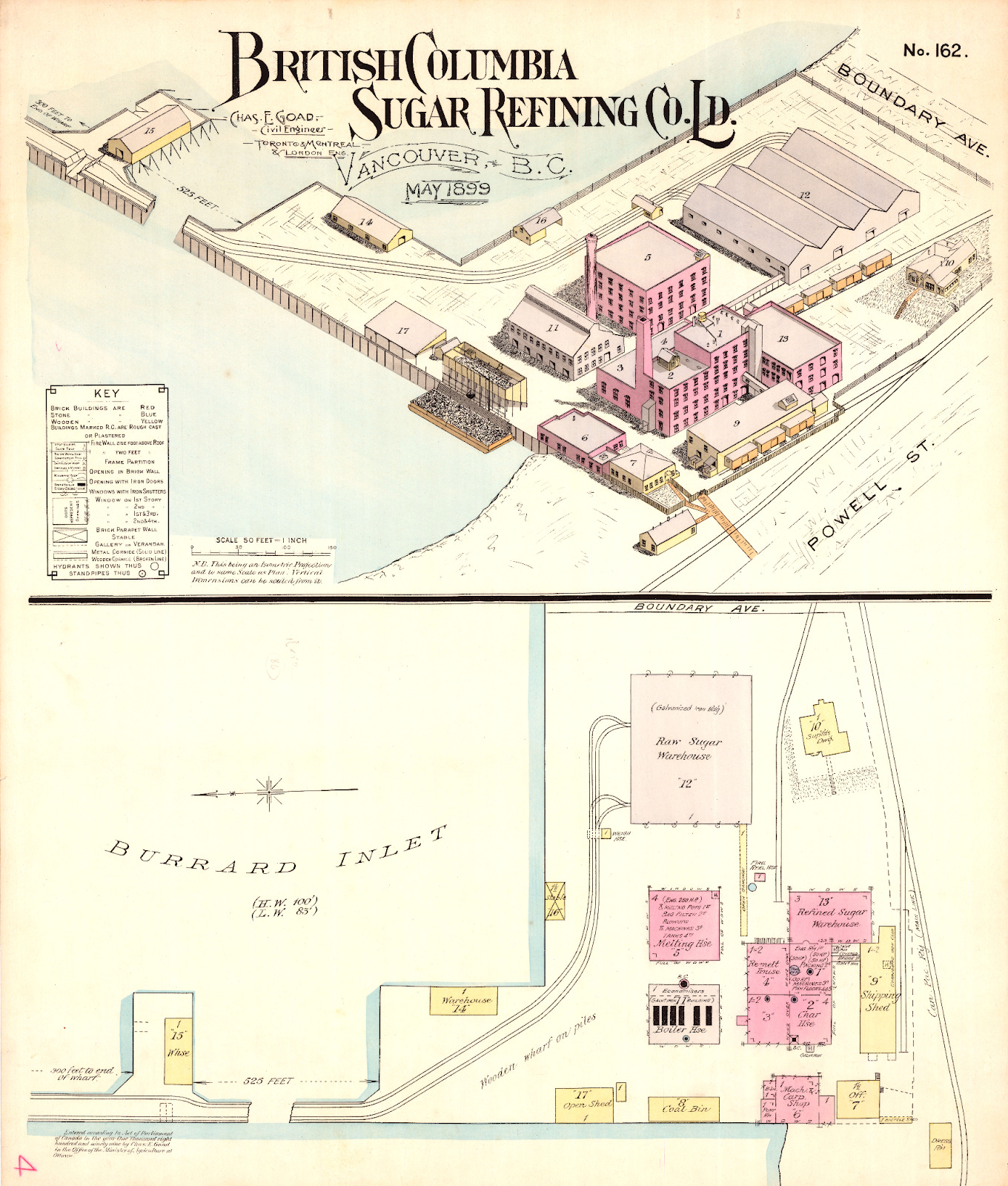

In 1975, the Rogers Sugar Factory was crowned the least attractive building in Vancouver. The adjudicator, an author at the Vancouver Sun, pointed to the “sheer force of its industrial ugliness”—and indeed, the building’s greyish, boxy exterior doesn’t exactly melt into East Vancouver’s waterfront.1

Charles E. Goad’s 1899 map of the building tells a different story.2 The sugar refinery is an inviting pink, with yellow splotches for the outlying buildings. The railway tracks wind gently from the refinery to the docks. The whole scene takes on a kind of industrial elegance.

Goad’s map had no reason to be visually pleasing. It was produced in 1899 as a fire insurance plan. The colours represent the material of each structure, while the isometric drawing helps show the heights of and distances between structures. Additional features—doors, windows, hydrants—are inscribed with special symbols. The plan was intended to help underwriters better estimate the risk of fire and price the building’s insurance accordingly. It is a beautiful document with a mundane goal.

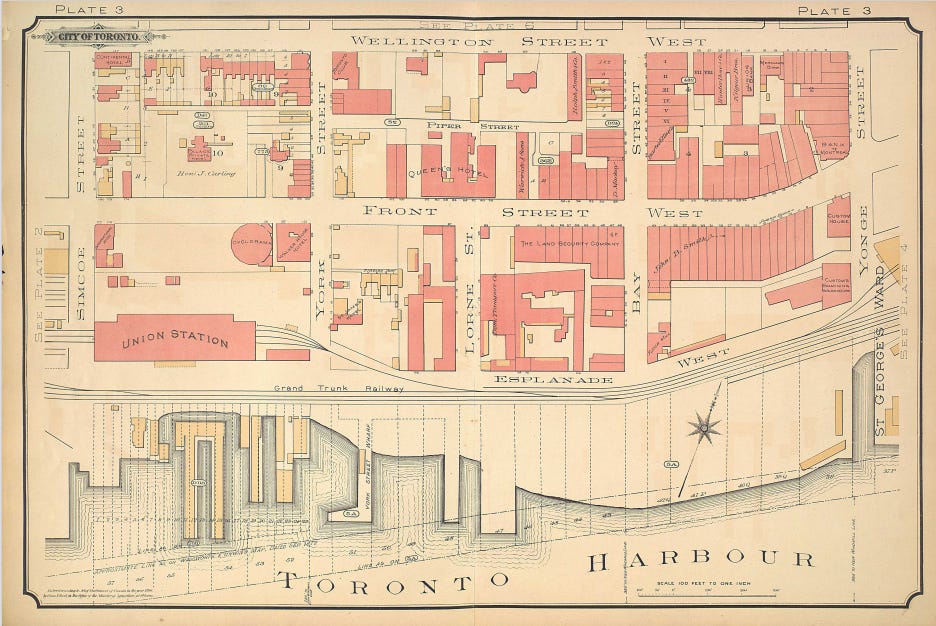

The sugar refinery was one subject of a growing collection of urban maps produced by civil engineer-turned-cartographer Charles E. Goad. Born in England in 1848, Goad worked in public infrastructure for several years before moving to Canada in 1869. He became a construction engineer for a railway in Toronto,3 and in 1875, he started a fire insurance mapping business based out of Montreal.4

Goad was a mysterious man. We know he was Anglican and attended St. Thomas’s Church,5 and we know he had at least three sons. Beyond that, information about his personal life is scarce. Goad gave few interviews and left behind few personal documents. Even basic facts—such as whether or where he went to university—are disputed.6

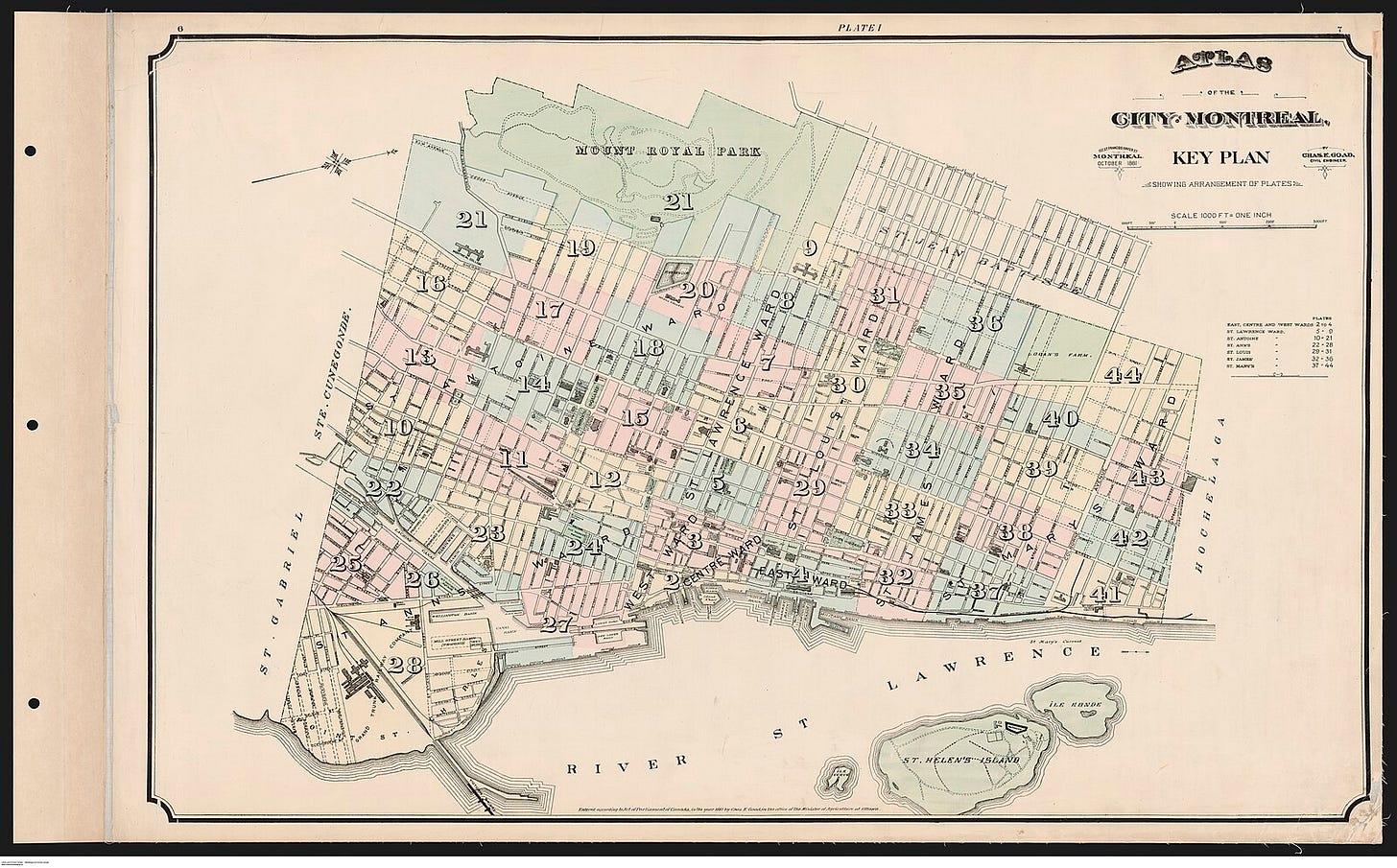

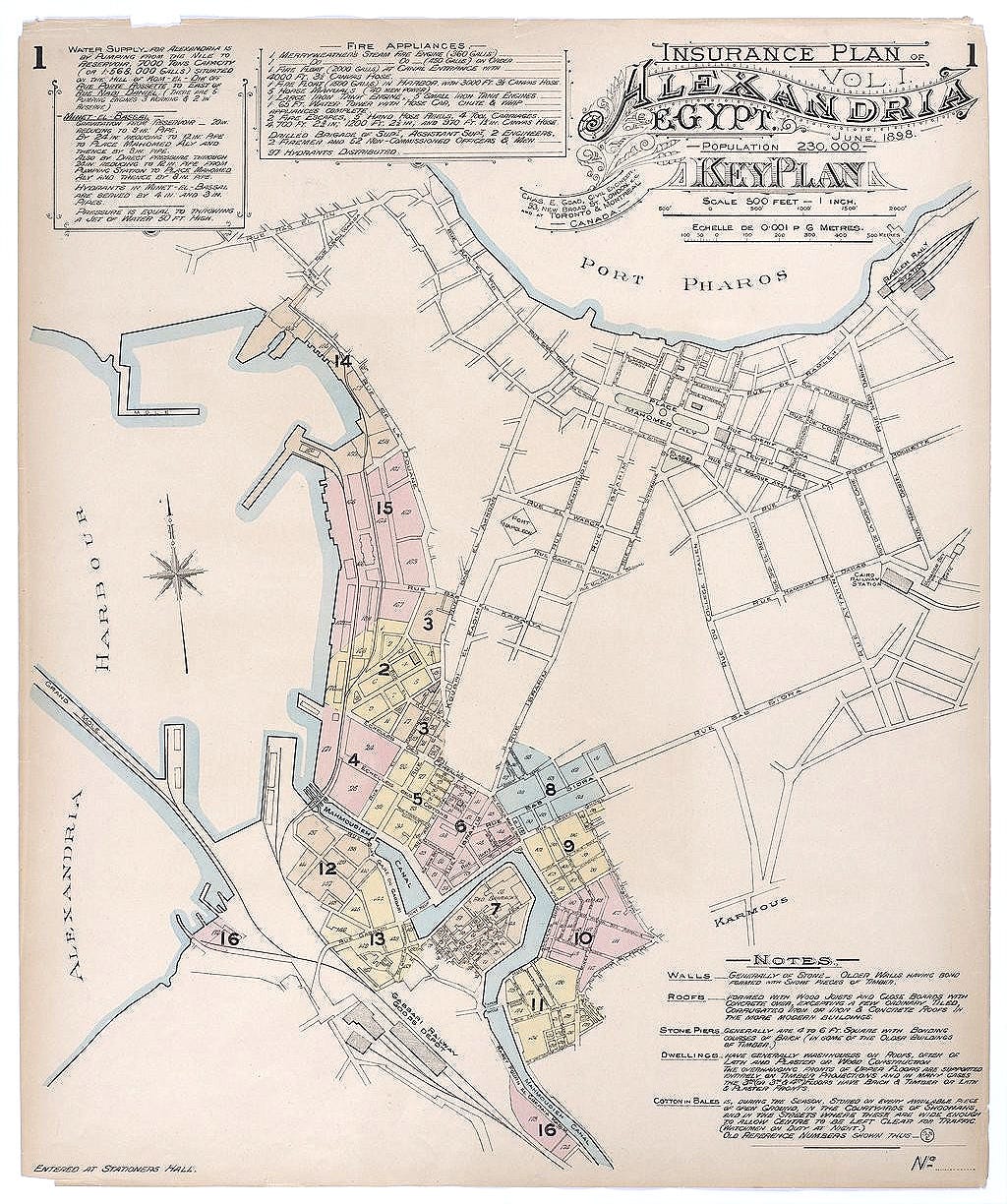

What Goad lacks in biography, he makes up for in maps. His firm had surveyed 340 Canadian towns and cities by the year 1885, and that year, Goad relocated to London and begin a British chapter of his fire insurance business.7 The company surveyed many cities within the Empire—Alexandria, Cape Town, Port of Spain—and some outside it.8 Each map was hand-coloured by Goad’s staff with the same pinks, yellows, oranges, and blues.9

The Goad maps were the culmination of a larger, centuries-long shift in how natural disasters were perceived. Prior to the Enlightenment, urban conflagrations were often seen as acts of God. A prime example is the 1666 Great Fire of London, which left 70-80,000 people homeless and was widely considered an act of divine intervention.10 “God speaks sometimes to a people by terrible things,” wrote Puritan minister Thomas Vincent in the opening words of God’s Terrible Voice in the City. Published one year after the fire, Vincent’s treatise attributes the disaster to Londoners’ “inward filthiness” and castigates those who behave with “sottish inconsideration of God’s dreadful displeasures.”11

The Great Fire of London marked the beginning of a more flammable era in British cities. Large fires—those burning at least forty or fifty houses—increased in frequency as urban populations expanded, wooden homes went up hastily, and stores selling flammable products proliferated near the Thames.12

With the rise of disaster came an urge for scientific understanding. Regulations on building materials, the invention of fire escapes and fire extinguishers, and, of course, the nascent fire insurance industry: all were part of a growing effort to understand and manage risk. By the mid-nineteenth century, “well over half of insurable property in Great Britain was insured against fire.” Scientific solutions to disaster did not necessarily contradict the belief in divine intervention: if disasters were a punishment for human recklessness, perhaps future punishments could be avoided with a dose of prudence.13

Great Britain’s scientific approach to natural disaster soon trickled down to its North American colonies. Canada, more so than the metropole, was a country built on wood. Its residents lived in wooden houses and “were sustained in large measure by the milling, fabrication, and export of wood products.” This reliance on wood gave way to several large urban conflagrations in the nineteenth century: Toronto in 1849, Montreal in 1852, Halifax in 1859, Quebec City in 1866, Saint John in 1877, and Vancouver in 1886.14 Goad’s maps of Canadian cities can be interpreted pragmatically as an effort to distribute risk. But they were also, in some deeper way, the mark of a society trying to understand and cope with an environment under threat.

D. A. Norris notes that Canadians “adapted” to fire hazards before “eliminating” them. That is, preventative measures meant to stop fires were introduced much later than insurance policies designed to handle the aftermath.15 Goad’s maps did both. They helped price risk more accurately; at the same time, knowing about the form and material of buildings helped identify ways to avoid future fires.

In 1899, Goad published a paper reflecting on major conflagrations in the previous ten years. He included 23 coloured maps of cities that had burned, including information on the fire’s path, causes of the fire, local wind speeds and direction. “Many of the sketches show the proverbial clearness of hind-sight,” the Globe reported. In Alexandria, fire-resistant doors might have contained an early fire in a warehouse. In St. John’s, a fire hydrant system was not filled with water beforehand.16 “The spread of fire insurance sometimes seems to invite the evident want of care that we oftentimes deplore,” Goad argued.

Goad, unlike some cartographers, did not believe his duty was solely to represent the world around him through maps. He saw himself as an agent of change. He called upon insurance companies to pressure cities into creating fire-resistant infrastructure by increasing insurance rates and refusing to insure dangerous buildings.17 He even financed a competition for children’s fables about fire safety.18 (Perhaps the most notable product of this competition was a story called “The Fire King’s Duty,” in which a reckless boy named Willie is burnt so badly that “when his friends came to look for [him] they only found his teeth, and the buckle of his belt.”)19

In 1910, Charles Goad died and was buried in Toronto. His company lived on under his sons’ leadership, but did limited work on new urban centres and stopped producing fire insurance maps altogether around 1918.20 In 1931, the Goad Company and its assets were bought out by the Underwriters’ Survey Bureau.21

Left behind by the company’s dissolution were thousands of painfully detailed maps produced by Goad and his staff. About two-thirds of the maps were destroyed,22 but those that survive offer a unique glimpse into urban life across the British Empire at the turn of the twentieth century. “A photograph captures a person or place at an instant in time,” wrote Frances M. Woodward, “but a fire insurance plan captures a whole community or industrial complex.”23

Goad’s maps reveal the cultural life of cities: the Chinese stores and washhouses scattered across Nanaimo; the domes of London’s cathedrals; the vast gardens of Alexandria.24 They also help us visualize how cities changed. Goad’s staff used correction slips and paste to modify maps when buildings were constructed or destroyed, creating a layered image of urban evolution.25 Recently, the maps have been employed once again to mitigate environmental hazards. Environmental assessors in Canada use Goad’s maps to locate sites of possible historical contamination—such as underground fuel storage tanks—and manage risk accordingly.26

Seen this way, the pink refinery on Goad’s 1899 plan and the grey monolith derided in 1975 are not opposites, but competing visions of the same object. The Goad maps captured a distinctly modern way of seeing the world—one that treated disaster not as fate, but as a problem to be measured, managed, and priced. There is something pleasantly idealistic about the belief that the city, for all its volatility, could be rendered legible using only paper, coloured pencils, and a stack of correction slips.

Zak Vescera, “Uncovering the Bitter History of Vancouver’s Sugar Refinery,” The Tyee, February 16, 2024, https://thetyee.ca/Culture/2024/02/16/Uncovering-Bitter-History-Vancouver-Sugar-Refinery/.

British Columbia Sugar Refining Co. Ld., Vancouver, B.C., May 1899, cartographic material, attributed to Charles E. Goad, Civil Engineer, Toronto, Montreal, and London, British Columbia Sugar Refining Company fonds, engineering and maintenance records, City of Vancouver Archives, reference code AM1592-S8-: 2011-092.0113.

Elizabeth Buchanan and Gunter Gad, “Goad, Charles Edward,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/goad_charles_edward_13E.html.

Gwyn Rowley, “British Fire Insurance Plans: The Goad Productions, c. 1885–c. 1970,” Archives 17, no. 74 (October 1985): 67, https://doi.org/10.3828/archives.1985.7.

“Charles E. Goad Dead: Was a Very Widely-Known Civil Engineer Originated the Idea of Preparing Plans for Insurance Purposes of All the Municipalities in Canada, England and South Africa,” The Globe (1844–1936), June 11, 1910, 8, https://search.proquest.com/docview/1429790534/.

Buchanan and Gad, “Goad.”

Jean Dryden, “Copyright in Fire Insurance Plans,” Archivaria 91 (Spring/Summer 2021): 153, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/795474.

Richard Haworth, “Review of British Fire Insurance Plans: The Goad Productions, c. 1885–c. 1970, by Gwyn Rowley,” Imago Mundi 38 (1986): 112; Charles E. Goad, Insurance plan of Cape Town, Cape Colony, South Africa (Cape Town: Entered at Stationers Hall, 1895), map, Stanford University Libraries, https://purl.stanford.edu/yc443cd2491.

Gwyn Rowley, Fire Insurance Plans, accessed via the Internet Archive, September 30, 2011, PDF, https://web.archive.org/web/20110930144424/http://www.mcrh.mmu.ac.uk/pubs/pdf/mrhr_03ii_rowley.pdf

“Facing Up to Catastrophe: The Great Fire of London,” Faculty of History, University of Oxford, https://www.history.ox.ac.uk/facing-catastrophe-great-fire-london.

Thomas Vincent, God’s Terrible Voice in the City: Wherein Are Set Forth the Sound of the Voice, in a Narration of the Two Dreadful Judgements of Plague and Fire, Inflicted upon the City of London, in the Years 1665 and 1666 (Bridgeport: Printed and sold by Lockwood & Bachus, 1811), 2-6, https://archive.org/details/101165066.nlm.nih.gov/page/n5/mode/2up.

David Garrioch, “1666 and London’s Fire History: A Re-Evaluation,” The Historical Journal 59, no. 2 (2016): 319–320, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X15000382.

Robin Pearson, Insuring the Industrial Revolution: Fire Insurance in Great Britain, 1700–1850 (Aldershot, Hants, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), 1-5.

Darrell A. Norris, “Flightless Phoenix: Fire Risk and Fire Insurance in Urban Canada, 1882–1886,” Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine 16, no. 1 (1987): 62–68, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43561851.

Ibid, 62-63.

“Conflagrations of a Decade,” The Globe (Toronto), June 19, 1899, 6, https://search.proquest.com/newspapers/conflagrations-decade/docview/1649978385/se-2.

Ibid.

“Beware the Blaze,” The Globe (Toronto), August 5, 1904, 7, https://search.proquest.com/newspapers/beware-blaze/docview/1356289467/se-2.

“A Fable for Children: The Fire King’s Duty,” Herald of Gospel Liberty 99, no. 41 (October 11, 1906): 663.

Haworth, “Review,” 112; Frances M. Woodward, “Fire Insurance Plans and British Columbia Urban History: A Union List,” BC Studies, no. 42 (Summer 1979), https://doi.org/10.14288/bcs.v0i42.1020.

Robert J. Hayward, Fire Insurance Plans in the National Map Collection = Plans d’assurance-incendie de la collection nationale de cartes et plans (Ottawa: National Map Collection, 1977), xi.

Ibid, xii.

Woodward, “Fire Insurance,” 20.

Insurance Plan of Alexandria, Egypt. 2 vols., 26 maps. London: Chas. E. Goad, 1898–1905. Fire insurance maps. American University in Cairo, Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.aucegypt.edu/digital/collection/p15795coll6/id/74; Charles E. Goad, Insurance Plan of London, vol. 1, sheet 10 (London: Chas. E. Goad, [late 19th century]), British Library shelfmark BL 152434, accessed via Wikimedia Commons; Charles E. Goad, Egypt. Alexandria. Key Plan (London: Chas. E. Goad, [late 19th–early 20th century]), accessed via Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Hayward, “Fire Insurance Maps,” xii.

“What Can We Learn from Fire Insurance Plans?” Sage Environmental Consulting, https://www.sage-environmental.com/what-can-we-learn-from-fire-insurance-plans/; “Fire Insurance Plans,” Groundsure, https://www.groundsure.com/fire-insurance-plans/.