"They will devour what little you have left"

In March 1915, Jerusalem faced an unlikely invasion. The invaders were heard before they were seen, reported John D. Whiting in National Geographic magazine. There was “a loud noise … resembling the distant rumbling of waves,” then a “sudden darkening of the bright sunshine,” he wrote. “At times their elevation was in the hundreds of feet; at other times, they came down quite low, detached members alighting.”

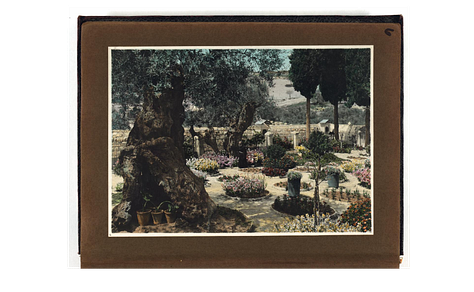

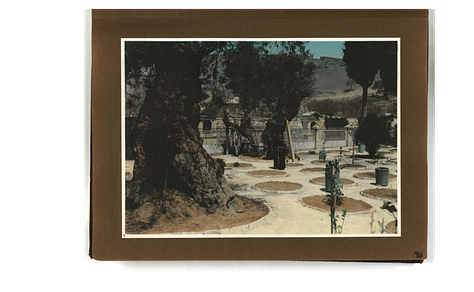

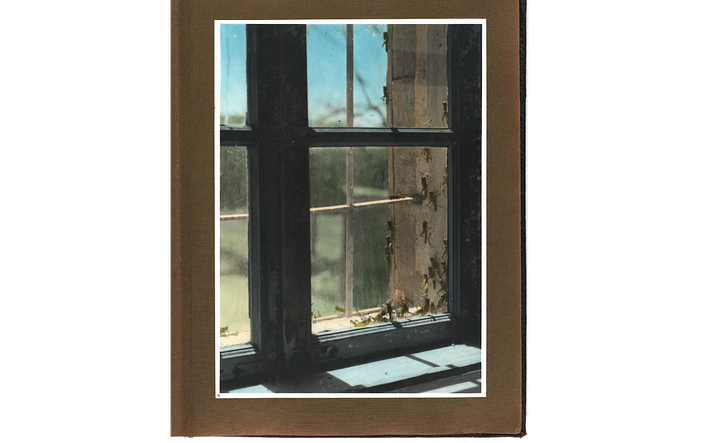

These invaders were smaller than Jerusalem’s past enemies. In fact, they were bugs. “Swarms of locusts had flown overhead in such thick clouds as to obscure the sun,” Whiting wrote. They flapped their wings loudly, showered excretions—“especially noticeable on the white macadam roads”—and snacked on the local orchards.

Why were there so many insects? Most of the Middle East’s deserts are home to the migratory locust, which lays its eggs in the sand. In dry weather, most of its eggs die. When it rains, the young locusts crawl out of the sand en masse and fly in swarms. Locusts are known for their “gregarious phenotype,” activated when they enter groups, which causes them to change colour, get faster, and travel together. In 1915, the Levant followed this pattern precisely. Its skies filled twice: first with rain clouds, then with beating locusts.

The locals didn’t know much about locust biology, so they blamed God. “God protect us from the three plagues: war, locusts, and disease,” wrote Ihsan Hasan al-Turjman, an Ottoman soldier stationed in Palestine. It wouldn’t be God’s first experiment with locusts, to be fair. In the Book of Exodus, the Pharaoh refuses to let the Israelites leave Egypt. “Stretch out your hand over Egypt so that the locusts swarm over the land and devour everything growing in the fields,” the Lord says to Moses. The locusts arrived soon after, and “covered all the ground until it was black.”

What the Levantines were being punished for in 1915, however, was unclear. Scripture did not provide a way out, and leaders were quick to embrace earthly solutions instead. Residents constructed large boxes and trapped the locusts inside. In Bethlehem, the locusts were buried in cisterns; in Jaffa, they were thrown to the sea, then used for fuel when they washed ashore.

In Jerusalem, the government deputized its citizens to fight locusts. Each person aged 15 to 60 was obligated to collect 20 kilograms of locust eggs, according to al-Turjman. Those who didn’t comply were fined: the rich had to pay one Ottoman pound, the middle-class paid 60 piasters, the poor paid 30 piasters. “I think the authorities did well with this edict (even though I hate them),” al-Turjman wrote. “The locusts do not discriminate between rich and poor.”

Their efforts were unsuccessful. For the better half of 1915, locusts ravaged the Levant. They weren’t picky eaters: they ate leaves, flowers, fruits, vines. They even burrowed their way into bee hives, “consuming honey and bees alike.” In total, the locust swarms diminished the region’s winter harvest by 10 to 15 percent, and its summer and autumn harvests by somewhere between 60 and 100 percent. Between 100,000 and 200,000 deaths from starvation are attributed to the locusts alone—not accounting for contemporaneous war, resource blockades, and the spread of disease.

Even al-Turjman, who had cautiously supported the government’s plan to fight locusts, grew despondent. He prayed to God in his diary and could “hardly walk in the streets.” It is perhaps this sense of fatalism that is most resonant with our contemporary reactions to humanitarian disaster. “Usually I worry about the smallest matter that can happen to me,” wrote al-Turjman in May of 1915, “but now with disaster visiting everybody, I have stopped caring.”